Interview with Miriam Aziz–a global artist

Miriam Aziz grew up in Brussels, Belgium and was born in England. She can speak English (mother-tongue) and French, German and Italian fluently. She began playing piano at the age of 5 and started writing songs at 11. By the age of 15 she was writing and performing her own material in a band called Foreign Affairs. In 1989, she moved to Manchester, England where she continued to write and perform songs whilst studying for a law degree which she completed in 1992. She went on to qualify as a lawyer in London and then moved to Edinburgh, Scotland to do a Phd in 1994, all the while playing and experimenting with all styles of music.

She moved to Berlin in 1997 and spent three years living there before she moved to Florence, Italy in 2000 where she started to work on songs for a debut album, We’re Inside Out which she released on her own label, Rock Pixie Records in 2007 which was produced by Malika Makouf Rasmussen (Exit Cairo and On Club) together with Women’s Voice Productions based in Oslo, Norway.

Miriam Aziz often collaborates with dancers and her music has been used in dance classes and productions. In 2008, she wrote a piece of music for Tancredo Tavárez, a former Martha Graham dancer who teaches Modern dance at the Béjart school (Ecole-Atelier Rudra Béjart) in Lausanne, Switzerland. Her work with dancers inspired her second album Tránsito which was released on October 26, 2009 on Rock Pixie Records in conjunction with New Music and Women’s Voice Productions, distributed by EMI MUSIC Norway AS.

In 2007, she worked with Scottish film director Richard Jobson, former member of the art-punkband the Skids (16 Years of Alcohol, A Woman in Winter, The Purifiers and New Town Killers) on the release of a video for Gypsy one of songs from her album We’re Inside Out, an experience which inspired her to experiment with film-making. In the autumn of 2009, Miriam moved to New York where she recorded an album called Muerte, Bailaremos (Rock Pixie Records) which was released on June 1, 2010 and which archives a pivotal stage in this journey of discovery.

We had an email interview Miriam

Q1. Tell us something about your early days. How you liked music and thought of picking it up as a career?

I was brought up in a household where music was an additional family member with a DNA which was as global as our origins (Pakistan, Tanzania, Austria, Great Britain). We listened to classical music – both western and Indian – jazz, rock and roll, opera, blues, French chansons, flamenco, pop music, Indian film music. We were taught to discriminate on the basis of quality, that is, does it, as I like to say, move your groove. That evaluation stretches internal and external geographical boundaries so that you are conscious of being open to question and answer. My parents gave me the gift of life on two occasions, at my birth and then by paying for piano lessons when I was 5. By the time I was 11, I was ‘composing’ songs and trying my hand at improvisation. I sang in the school choir, and played percussion in the school orchestra, brass and jazz ensemble. I remember the sense of freedom, of finding a sense of place, of belonging, if you will, through music. Although I was taught to read music, I also played by ear – and would try to recreate the music that was all around me, both at and away from home. I knew that music would be part of my life – though I could not yet imagine how that could be translated and transposed in terms of a career.

Q2. Tell us about your training and how you liked those days. How was the experience to devote so much time to music?

I started taking piano lessons when I was 5 years old with a severe Russian pianist called Madame Unterberg who had a great sense of humour (luckily for me!). I was a conscientous student until I started to improvise with ideas I had about jazz – they were only ideas at that time, as I was only starting to discover it through the radio and my drum teacher Jan de Haas in whose school ensemble I also played. Mme Unterberg did much to discourage this type of experimentation so I eventually changed teachers and studied with Rosamund Angel, who accompanied me in my forays into – and beyond classical music as a guide, a philosopher and later, as a friend. I was also playing in the school orchestra, band and jazz ensemble, and taking drum lessons. When I was 15, I organized my own band called “Foreign Affairs” as I was also starting to teach myself the guitar, and experimenting with song writing. I worked hard – but I was rarely aware of time, as it was not work for me, but a way of journeying through life. Although I say that with the benefit – and burden – of hindsight!

Q3. How you managed studying and practicing music at the same time?

Strict time management and setting priorities. I studied law and became a barrister and a professor of law. That meant many years of study which are ongoing. Law and music are vocations, and must be practiced each day. The more obligations you have, the harder it is to carve out time – it must be done, however, and I still do my scales each day! Needless to say, I don’t own a television.

Q4. How much do you like the element of experimentation within your music? Does it help you to evolve as a musician?

I love improvisation and experimentation. My last album, “Muerte, Bailaremos”, which I released on my own record label, Rock Pixie Records, was designed around some themes and then recorded with a group of musicians I met in New York in two takes. It was exciting, exhilarating and terrifying. It also affected my performance – as I started to search for that type of edge during my concerts. I particularly enjoy experimenting with my voice, trying out different types of phrasing which provokes and promotes the music amongst the musicians and amongst the listeners. I have also experimented with dance, theatre and film, which have both enabled me to explore separate yet related dimensions of art. This is necessary in order to avoid stagnation. You need to be in a place where even repetition becomes a new act of creation.

I have recorded and performed with world renowned musician Malika Makouf Rasmussen, both in Italy and at Oslo’s Mela festival in the summer of 2009. She also produced my first two albums, “We’re Inside Out” and “Transito”. You could say that she mentored me and taught me a lot about being a professional musician who never ceases to remain curious. I owe her a debt that I am unable to repay. She believed in me at a turning point in my life – that is to say, the moment I decided to commit to being a professional musician.

If you want me to name drop further, I could also mention Tony Levin (who is Peter Gabriel’s bass player), Stefano Coco Cantini (one of Italy’s top jazz saxophonists), Bugge Wesseltoft (one of Norways top jazz musicians). The list goes on and I have played with so many great musicians in Norway, Italy, France and the United States – my antennae are always on the alert for musical encounters, and it is a driving force in my life – communication through art. I thrive on the experience which always teaches you about yourself and the world we live in, through different interpretations of my music. Each concert is slightly different, depending who I am performing with. My band in New York is more centred around who and how we are – the vibe is more jazz, flamenco and funk, but we do invite other musicians to play with us and have, for example, had classically trained musicians improvise with us, which drives the music in different directions.

Q6. What do you feel is the true satisfaction point for an artist—winning awards or winning hearts? What personal satisfaction do you seek in your music?

I never really thought about winning awards, although I am thrilled to see musicians I admire and who have been a source of inspiration to me get the recognition they deserve, all the while being aware of the fact that so many, if not most, musicians struggle through their careers without any official recognition whatsoever. Awards should also go to them – even if you think it, as you pass a musician who is playing in the street or the subway, or a crowded restaurant where no-one cares to listen.

The personal satisfaction is driving yourself to a place which is beyond your own imagination, where you are in tune with a part of the universe you can’t name, and you can’t even see but you know that it is there through how you feel. It is as though the music speaks through you and you lose your sense of self. That may sound a little vague – but I assure you – when you get to that place, you’re home.

Q7. How do you feel music has helped you to evolve as a better human being?

I am not sure that I would like to think in terms of ‘better’ human beings. I think that music has helped me to remind myself of my basic humanity – and has enabled me to travel, as an individual and as a member of the global community to places, people, emotions, ideas and concepts. It has accompanied me through journeys through states of being, if you will.

Q8. Tell us what else you like to do while not playing music.

I take dance classes (ballet and modern), I make short films, I write short essays which I sometimes include on my blog (at wordpress.com); I read, I enjoy going to the cinema, and to theatre and dance performances.

I am also an academic (law) and am conducting research on international law and human rights, health care law and global copyright law.

Q9. Tell us about your professional career as a lawyer. Do you practice it on regular basis?

I gave up legal practice some years ago although I occasionally do some consultancy work. I am, however, a law academic which means that I conduct research and I also teach. I am currently a visiting scholar at Columbia Law School in New York.

Q10. What message you would like to give to the readers and young aspirants of music?

To young aspirants of music, I would say, do your scales! And most of all, understand why you need to do your scales and while you’re at it, why you must practice each day. Whether you wish to be a professional or an amateur musician, be disciplined about your musical apprenticeship but don’t forget to experiment, to improvise, and to have fun.

To other readers, I would say, try to take time to really listen to the music around you, a song, a symphony, musicians practicing, the rattling of a subway car, or children laughing at a playground, as they swing higher and higher. Set aside the time to dedicate yourself to listening – try to avoid relegating music to background noise. If you can manage that, you will start to cherish not only music but also yourself, and by extension, your fellow man. We all need reminding of the need to listen what others have to say and moreover, how they say it.

Single Review—Spiraling Up

Single Review—Spiraling Up  Album Review—Inner Sanctum

Album Review—Inner Sanctum  Album review—Back To My Roots

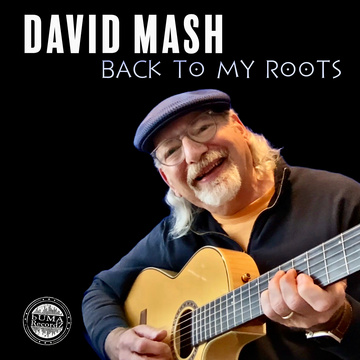

Album review—Back To My Roots  Album Review—Days of Gypsy Nights

Album Review—Days of Gypsy Nights